Keewatin and the Deconstruction of J.S. Woodsworth

The Muse Newsletter

Vol. 31 No. 3 – Summer 2021

by Braden Murray

There was excitement in the air in Kenora on October 4th, 1938. The leader of the Co-operative Common-wealth Federation (CCF) J.S. Woodsworth was having a rally at Derry’s Palace Theatre. After the first few speakers, the packed-in crowd fell silent as the slim politician took the podium. Though small in stature, his presence filled the vaudeville theatre as he rallied his supporters. After a brief introduction, Woodsworth strayed from his prepared remarks briefly to remind the crowd that this was not his first time addressing a local audience— thirty-seven years prior he had been a pastor at the Keewatin Methodist Church.

J.S. Woodsworth, politician, labour leader, and founder of the CCF, had one of his earliest assignments as a pastor at the Keewatin Methodist Church from the fall of 1901 to the summer of 1902. It was during his time in Keewatin when he began to wrestle with the ideas that would inform his work for the rest of his life.

James Shaver Woodsworth Jr. grew up in Brandon, Manitoba as the son of a Methodist preacher. In 1895, at the age of 21, Woodsworth took his first step in following in his father’s footsteps in the ministry by becoming a lay preacher on the Manitoba circuit. After two years he left to study, first at Victoria College in Toronto and later at Oxford University. After graduating, Woodsworth was ordained as a Methodist minister in August 1900.

After spending a year as a student pastor in Carievale, Saskatchewan, Woodsworth was transferred east to the Keewatin Methodist Church in Keewatin, Ontario. It was in Keewatin where Woodsworth began what we would know now as “deconstruction”. The term “deconstruction” is a modern way of describing the process that many 20-somethings go through when they take the religious ideas they learned growing up and break them down and re-organize their beliefs. This has also been described as the process of “spiritually re-arranging the furniture” or “pulling at the loose threads of belief”. This process can often leave people with very different-looking beliefs than they started with.

During the long, lonely winter in Keewatin, Woodsworth struggled with a congregation he viewed as disengaged and apathetic. He spent much of his time reading, and began to question the inerrancy of the Bible – like did New Testament miracles actually happen? He also began to question the idea of the Holy Trinity and the divinity of Christ. More importantly, he began seriously considering the ideas of the “social gospel” movement— the idea that saving someone’s soul, while ignoring their practical day-to-day needs, was not true Christianity. The idea of the “social gospel” informed Woodsworth until the day he died.

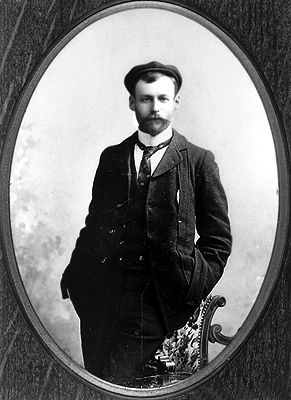

J.S. Woodsworth

We know about Woodsworth’s “deconstruction” during this time because of letters he wrote to his cousin, C.B. Sissons. In a letter from Keewatin in February, 1901, Woodsworth wrote, “You know I am dreadfully heretical on many points… Next year I should like to get to Winnipeg for some city mission work.” Woodsworth was not ready to abandon the social work of the church, but he was already feeling that day-to-day pastoral work was not for him, largely because of his new beliefs.

Despite his changing views, Woodsworth still dutifully fulfilled his role as a young pastor in small town Ontario, though he would avoid speaking on topics that would cause him to have to preach what he did not believe. In January 1902 he was one of the leads during the local Ministerial Association’s Week of Prayer event. He spoke three evenings that week— On Monday at Zion Methodist Church in Rat Portage, Tuesday at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Rat Portage, and finally Thursday night at Keewatin Presbyterian.

Despite outward appearances, J.S. Woodsworth was increasingly unhappy in Keewatin. He was disappointed that people in Keewatin were not interested in digging into the intellectual side of Christianity or really any intellectual pursuit, and visitors from Winnipeg were not much better. His salary of $500 a year was hardly enough to live on and his prospects for marriage were nil. To put it bluntly: he had no wife, no friends, and no money. In addition he was getting no satisfaction from his work— he wrote to his cousin complaining about how he felt the church wasn’t doing enough to actually make people’s lives better here on earth and that, “we struggle to keep up congregations to please cranky people — and for what?” Clearly something had to give.

After less than a year in Keewatin, J.S. Woodsworth had had enough. He drafted a letter of resignation and had it in his pocket when he attended the 1902 Methodist Annual Conference. The resignation was never delivered. Woodsworth’s father sensed his son’s frustration and arranged to have him transferred to Grace Church in Winnipeg. It was at Grace Church in Winnipeg that Woodsworth began moving toward his work with the poor and advancing the social gospel in practice.

J.S. Woodsworth’s work saw him become a powerful advocate for the poor, immigrants, and the marginalized in society. He was a leading figure in the Winnipeg General Strike, and was elected federally to represent Winnipeg North Centre in 1921, a riding he held until his death in 1942. From this position he was able to bargain with Prime Minister MacKenzie King to implement one of the first building blocks of Canada’s social safety net— the Old Age Pension Plan. In 1933 he brought together progressives, social gospellers, and socialists to form the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation— one of the precursors to the modern NDP. Woodsworth was widely respected across party lines, and PM MacKenzie King nicknamed him the “conscience of Parliament.”

Though J.S. Woodsworth’s time in Keewatin was short, it was no doubt impactful in his life. It wasn’t necessarily the most positive experience for Woodsworth, but it was formative. During the long, cold winter of 1901-1902 J.S. Woodsworth had time to deconstruct his faith and then begin to reconstruct a new belief based on the ideas of the social gospel. These ideas propelled him to national leadership and laid important groundwork for Canada’s political left that continues even today.

Did you know?

The Lake of the Woods gold rush in the 1890s brought miners and investors from across North America. By 1893 there were 20 working gold mines on the Lake of the Woods.