The Burley Mine

Muse Newsletter

Vol. 33 No. 2 – Spring 2023

by Lori Nelson

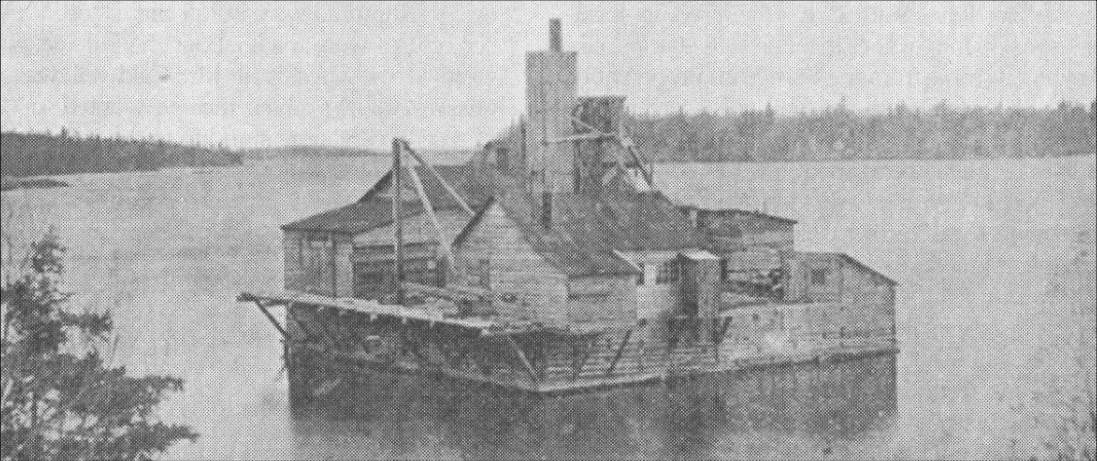

The Burley Mine.

To the south and west of the still-visible slag pile of the former Sultana Mine is a small island. From afar it looks like any other Lake of the Woods island. Its shoreline is rocky and it’s overgrown with brush and small trees. However, if you were to have an aerial view of it, you would be struck by its shape – a well- defined square. And if you came close to it, you would see the wooden timbers that give it its form.

The story of this little man-made island dates back to the 1890s. Gold had been discovered on Lake of the Woods and within a few short years there were 20 working mines located on the lake, the majority being found in the Shoal Lake and Bigstone Bay areas. Sultana, the largest and most productive of the mines, was benefitting from the rich Crown Reef vein.

Reasoning that the moneymaking vein was not restricted to the confines of Sultana Island, J. Burley Smith, manager of the Burley Gold Mining Company of Ottawa, wisely surmised that the Crown Reef vein extended into the bay and so the company acquired the water rights. Legal wrangling began between Smith and F. Caldwell, owner of the Sultana Mine, but in the end, the courts ruled in favour of Smith. He could lay claim to the underwater vein. Accessing it became the next challenge.

In the fall of 1897, a large wooden crib was built on Queen Bee Island, which was just across the bay. The crib was 60 feet square. Another crib, 40 feet square, was also built to fit inside the larger one. The inner structure was braced and sheeted with 8” square timbers. In total, it took about 2 months to build the 24.5 foot tall frame. In November, the crib was hauled by steam tug to the proposed site of the shaft and tons of broken rock were used to fill between the inner and the outer cribs, sinking the shaft to the bottom of the lake.

Waterproofing of the submerged shaft was done with oakum, concrete and cement. Water was kept from the inner crib by a steam centrifugal pump with a capacity of 2,500 gallons per minute. A machinery building and pit head frame were erected on the crib’s deck platform.

The bedrock was accessed through this wooden- constructed shaft and from there the shaft dropped another 105 feet to the first level and another 70 feet to the second level.

The mine operated until June of 1899 with a crew of about 22 men who lived in camps built by the company on Queen Bee and Chien d’Or Islands. The ore was brought to the surface in cages and was then loaded onto barges and taken for processing, likely to the Keewatin Reduction Works.

When the mine was closed in 1899 by then manager P.W. Webster, the shaft filled with water. Eventually ownership of the mine was transferred to the Coronation Gold Mining Co. Ltd., and in 1903 work commenced once again at the site. The shaft was sunk to 202 feet, however, water leakage into the shaft was a significant problem and although a crew of men was recruited to keep on the pumps, the water could not be lowered below the first level.

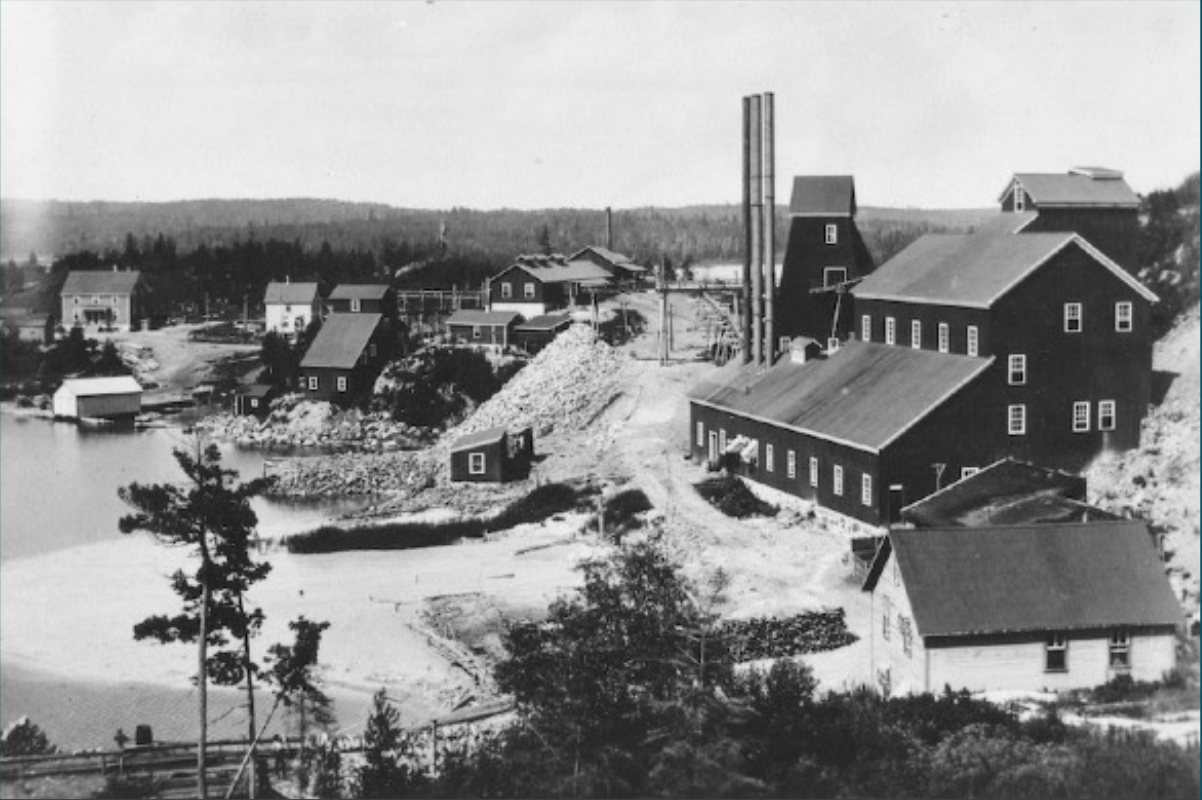

As you can see from this image, the Sultana Mine was a going concern with a whole community that grew up around its operations. It was, for a time, one of the largest producing gold mines in Ontario.

The profitable gold vein that ran under Sultana Island also extended under the lake at the southeast end of Bald Indian Bay. It was there that the Burley shaft was sunk in order to access the rich gold vein.

Two of the men on pumping duties were Harry MacFie and Sam Kilburn. MacFie wrote years later of the mine:

The big pump worked for a full twenty-four hours, sending its masses of water through a hose-pipe out into the lake. We gained on the water, but it was slow work, and the rotten timber groaned and creaked when the pressure of water outside increased. The walls leaked everywhere; the water poured through the chinks between the muddy logs and down into the shaft. Sometime regular subsidences in the timber structure were felt which made us feel that it would not withstand the pressure, but would collapse. But it still held, and the water sank slowly but surely.

Until it didn’t. MacFie’s story, “The Mine Under the Lake”, ends in a dramatic account of him being caught in a large barrel inside the cribbed shaft as he was lowered to investigate the malfunctioning pump. A series of mishaps and miscommunications with Kilburn on the hoisting mechanism made for a frightening account but MacFie was pulled to safety by Kilburn and regained consciousness while being transported by birch bark canoe to the hospital in Rat Portage (now Kenora).

The rest of the story was finished by Kilburn:

…I felt the island quake worse than it had ever done before. At the same moment I heard a loud roaring…The roaring came from the shaft; the water had breached the walls and was plunging down. I rushed in and dragged [MacFie] down to the boat. Just as I pushed out from the island one side collapsed with a tremendous crash. In a short time the masses of water filled the mine; the boat was almost carried away by them, but luckily I was already outside the worst suction.

The Burley Mine wasn’t in operation long – from 1897-1899 and 1903-1904 – before its hair- raising destruction. It was, however, considered one of the principal mines on Lake of the Woods in the 1890s. The evidence of its rare existence is a small square-shaped island in Bald Indian Bay.

Did you know?

Kenora’s Huskie the Muskie was built as a special roadside attraction during the building of the Trans-Canada Highway in the 1960s. The name Huskie was chosen because it was submitted with a slogan: Huskie the Muskie says, “prevent water pollution”