The Community Centre

Lake of the Woods Museum Newsletter

Vol. 29 No. 1 – Winter 2019

by Marcus Jeffrey

“You can take the ice out, you can take the seats out, or leave the roof off to arrive at a certain figure; but the people were sold on the whole project.” The words of Mayor Norton cut through Council’s debate on the evening of October 12, 1965. At issue was the construction of Kenora’s Centennial Project, the Community Centre.

Known today as the Kenora Recreation Centre, and incorporating a wide variety of fitness amenities, the Community Centre was originally meant to modernize the town’s deteriorating arena. The historic Thistle Rink, located at the site of the present federal building, had been in operation since the early 1920s. It was, by the 1960s, widely considered antiquated and insufficient for the recreation needs of the town.

The need for a new recreation facility, particularly for a new arena, was generally accepted; Kenora had a proud sports history, after all, and its youth were being shortchanged. Agreeing on a means of acquiring such a facility, and what it should look like, however, proved to be much more challenging. Three separate fundraising drives were attempted, but ultimately failed to reach their goals.

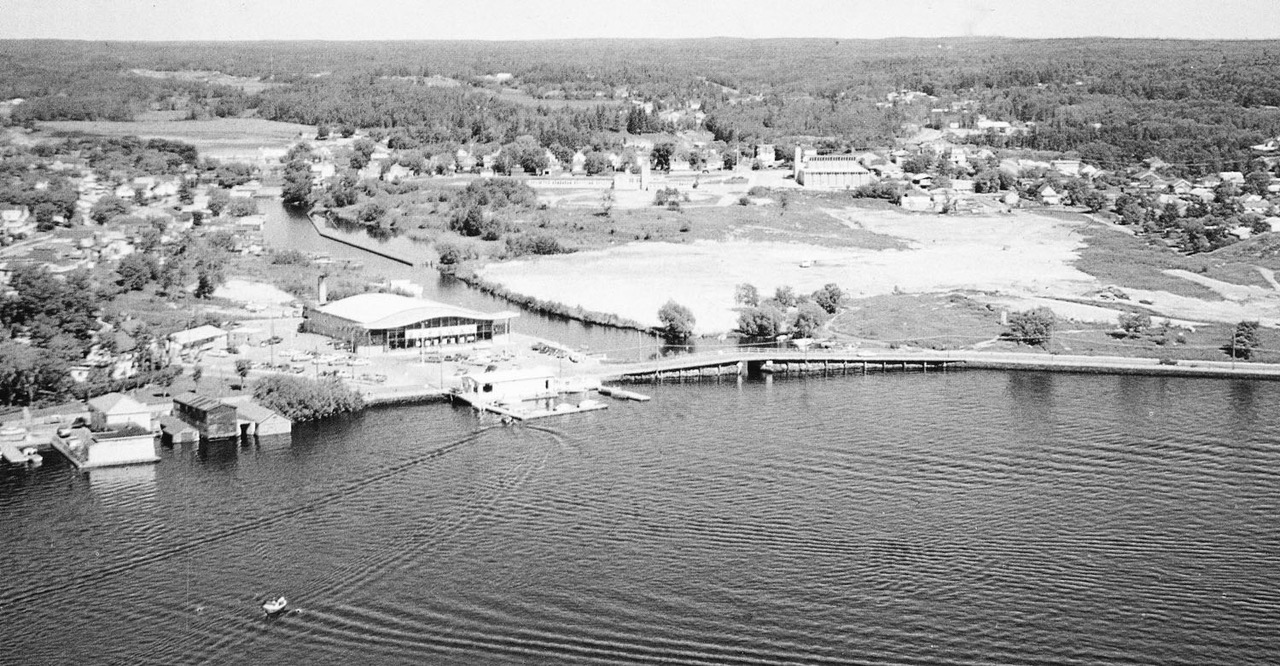

The site selected for the Community Centre.

There were a number of items to consider. For instance, which amenities should the new community centre provide? A rink, of course, but many voiced their concerns in the Miner and News that to truly be a “community” recreation centre, it should support other activities, too. Games rooms, tennis courts, a club space for teenagers, a ball field; these items quickly expanded the initial scope of the project.

Another question, posed early on, was whether or not the arena should use artificial ice. Perhaps the most widely-shared opinion was that the ice season was far too short to meet the needs of the local sports programs. Although there were several well-supported community clubs in Kenora — including (but not limited to) Evergreen, The Rideout, Norman, and Pinecrest — there were no artificial ice surfaces. In order to preserve and grow Kenora’s proud winter sports heritage, an ice plant was deemed to be an essential feature.

The Community Centre under construction.

Location, thankfully, was less of a concern. In the 1920s, Laurenson’s Creek was an industrial hive of activity, buzzing with the sounds of a lumber mill, and a sash-and-door factory. A spur line ran down the lane beside Matheson Street and along First Avenue South, linking these operations with the Canadian Pacific Railway. By the early 1930s, however, both the mill and factory had ceased operations and burnt down. Today’s Safeway grocery store is located roughly where the sash-and-door factory was situated — this was the first of the two sites to be redeveloped.

In the years following the lumber mill’s closure and destruction, its site became a landfill. By 1965, however, this area was being converted into a recreational space, to be ready for the summer of 1966. The site was identified early on as a good location for a new community recreation centre, a fact made more evident by the rapidly growing list of planned or projected amenities to be accommodated.

Despite the Town’s preference to set this site aside for a Community Centre, other groups were eager to move in as well, and it would not be held indefinitely. In March of 1966, for example, Kenora’s Judo-Kai Club presented to Council their proposal to relocate to the Mill Site. While the Judo-Kai Club’s proposed move to the site would not necessarily imperil the Community Centre, their presentation added more urgency to the project’s realization.

Perhaps the most important question concerned funding. How was the Town going to pay for the recreation centre? Before the Centennial Project’s initial planning phase in 1964, there had been no fewer than three failed attempts to raise money for a new recreation centre.

After a year of research and planning, the fundraising campaign was officially approved to start in April 1965. Although most donations from the previous, unsuccessful drives were refunded over the intervening years — four years had passed since the most recent attempt — some money remained, having come from community events such as raffles or hockey pools.

Roughly 150 canvassers went door to door, soliciting pledges for the new centre. Teens from local schools created posters for the campaign. Service clubs and credit unions added their financial support. Editorials were published by community leaders, extolling the virtues of pride in, and loyalty to one’s community. If Kenora was to become a year-round recreation destination, every able citizen would need to do their part.

The hope was to have the structure completed by the summer of 1966. This created a tight timeline, since the building was designated as Kenora’s Centennial Project, and therefore eligible for certain government grants. In June of 1965, Council announced that the project would be opened to tender in September of that year, but only if the fundraising committee could raise at least 90 percent of its goal. The success of this project depended on an efficient fundraising campaign, coming to a close before the tender opened.

As the deadline approached, it became clear that the fundraising campaign was not going to meet its goal. A plan to cover the funding gap was outlined to Council in September of 1965 that called for a combination of private sector fundraising, and financing from the Ontario Municipal Board; as well as assistance from the Municipal Works Program, the Winter Works Program, and a grant from the Community Centre Act, which supported projects across Canada.

The deadline passed. Though the fundraising campaign had not met its goal, the Committee urged Council to open the project to tender anyway. Significant funding opportunities were at risk if the project was delayed. Government funding would only cover costs already incurred, and most of the construction had to be completed during the winter months to take advantage of Winter Works funding.

Fearful of losing the project, the Committee proposed counting proceeds from the future sale of the Thistle Rink as a pledge. It suggested applying for further grants, including from the Federal Department of Indian Affairs. In an effort to cut costs, it even revised the recreation centre’s plans, dramatically scaling back the project. Of the many items proposed for deferral by the Committee, the most divisive was the artificial ice plant. This was a deep cut, but the public had already been burnt by numerous failed pledge drives — this was, the Committee argued, the last chance for the project.

The Committee’s arguments swayed Council, and they approved a loan to the project, making up the funding gap. The tender was opened, and a bidder was selected — the project would move forward. All seemed well, and years of hard work by the various fundraising Committees and teams was about to pay off. An editorial in the following day’s Miner and News proclaimed that Council, by approving the loan, had backed down on their original requirement that 90 percent of funds be raised before proceeding, and “arrived at the right decision by the wrong route.”

The ice-skating rink inside of the new Community Centre.

Then came the dramatic twist, befitting what was to be a municipal election year. At a poorly attended meeting on the evening of October 12, 1965, Council prepared to pass a by-law to enter into a contract with the project’s successful bidder. During the second reading of the by-law, then Alderman (and future Mayor) E. L. Carter eviscerated the plan to enter into the contract with so few funds realized. Leading Council through his arithmetic, the Alderman estimated that this significant project was likely supported by less than 25% of the rate-paying property owners in Kenora.

After much back and forth, including this article’s opening statement by Mayor Norton, it became apparent that Council was not prepared to move forward. After a wild year of fundraising, and so much positive momentum, the by-law was not passed, and the Community Centre project was shelved. Two months later, while outlining his election platform, mayoral candidate E. L. Carter clarified that he was always in favour of the Community Centre; just not by using large sums of money without ratepayer approval.

Despite the significant setback, thought at the time to be jeopardizing the entire project, the fundraising campaign continued. In February 1966, the freshly elected Mayor and Council expressed renewed support for the Community Centre, and a revised fundraising deadline of May 31st was set. The winning bidder for the Community Centre project had agreed to keep their bid on the table for six months.

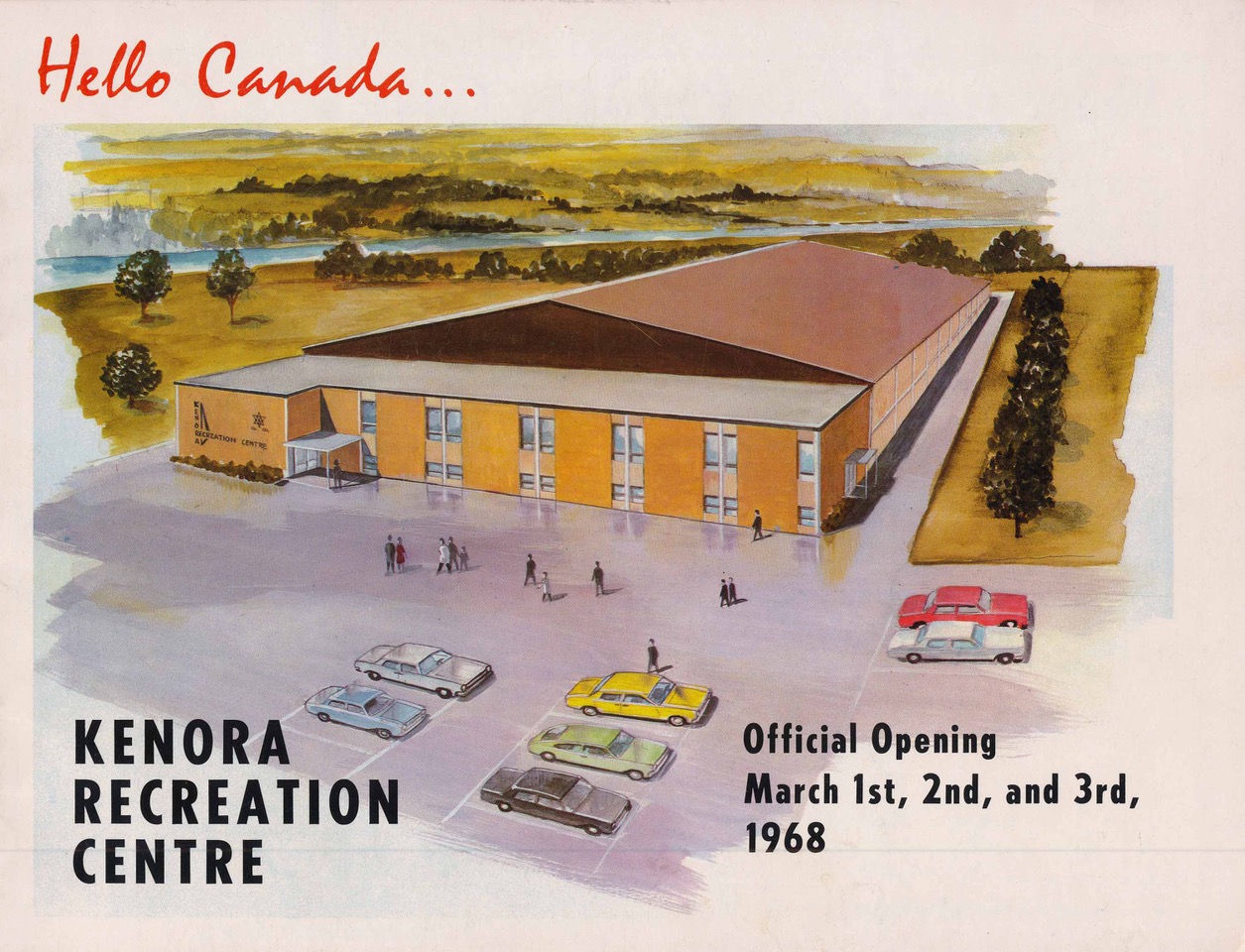

Promotional ad for the new Kenora Recreation Centre.

That spring, the Municipal Development and Loan Board approved financing for the project, and the Kenora Rink Company announced that proceeds from the sale of the property, when it occurred, would indeed be directed to the construction of the new arena.

Buoyed by the significant progress achieved to date, the public responded to the Community Centre Committee’s call for donations. As local high schools competed in fundraising drives, the business community did its part. Finally, at the eleventh hour, The Ontario-Minnesota Pulp and Paper Company announced a significant contribution to the project. Kenora’s Centennial Project, the Community Centre would indeed be built as planned.

After the Thistle Rink was transferred to the Town, deemed unsafe, and closed in September 1966, ongoing discussions for sale of the downtown property accelerated. The Federal Government, long considering a new building in Kenora for a post office and customs bureau, agreed to purchase the former rink site, effectively ending all doubts of the Community Centre’s future.

The Community Centre was part of a wave of construction projects in Kenora surrounding the Centennial Year, 1967, including the Lakeside Inn, the Federal Building, renovations to the courthouse, Lakeside Baptist Church, and — of course — Husky the Muskie. Slightly delayed, the Kenora Recreation Centre opened its doors in March of 1968, and is currently in its 50th year of operation. Like the town itself, the Recreation Centre has undergone numerous changes over the years, but continues to be a celebration of community spirit, determination, and pride.

Did you know?

Kenora was once claimed by Ontario and by Manitoba. Both provinces claimed the area between 1878 and 1884. The case was resolved in 1884 by Queen Victoria’s Privy Council, the highest court in the world at the time.