Spring Break-Up

Lake of the Woods Museum Newsletter

Vo. 25 No. 2 – Spring 2015

By Lori Nelson

The freighting of supplies to the south end of the lake was dependent upon the steamboats and the sooner they could get through in the spring, the sooner provisions could be delivered.

Each spring the gradual disappearance of ice and the subsequent opening of navigation on Lake of the Woods was carefully tracked. Rupert Donkin was just one among many who kept a personal record of spring break-up. Even for those not inclined to keep a diary, news of the ice thawing into lake became public record.

Columns like “Marine Notes”, “Among the Ships and Mariners”, and “Waterfront Flotsam”, began to appear in the local newspaper in April, noting which boats were being worked on and which were going to operate during the season.

A log of the opening and closing of lake navigation from 1907-1942 shows that while the first or second week in May was the usual opening date, it varied considerably from year to year. The years 1907 and 1910 mark the extreme ends of the record. In 1907 the steamers didn’t get out of the harbour until May 29th. Three years later, they were down the lake by April 23rd.

The difference of a week, let alone a month, was crucial to a lot of people.

The boat yard prior to the spring break-up.

On May 10, 1895, the Edna Brydges, a 75-foot steamboat equipped for lake and river trade, left Rat Portage and headed south for the Rainy River. While the heavy spring run-off meant high water and relative ease of travel up most of the river, such was not the case when the steamer reached the roiling Sault Rapids.

The Edna Brydges plowed through, making inch by inch headway until five hours later she emerged into the tranquil headwaters at nightfall. It was decided to overnight there and proceed in daylight.

When morning dawned, the Edna Brydges went head-to-head with the turbulent Manitou Rapids. After a seven hour struggle the exhausted crew and steamer pulled through and limped into Fort Frances at dusk. It was an important arrival, for winter had been very difficult for the settlers. Out of necessity many of them had to subsist on a diet of jackfish. When the Edna pulled in, her cargo of supplies was quickly unloaded and distributed to the grateful homesteaders.

The Edna Brydges.

THE COMPETITION

Besides the necessity of the opening of the lake for transportation and communication purposes, there naturally developed a competition to be the first boat to navigate through the ice floes in the early spring. Often the earliest steamers out were responsible for opening navigation in what became known as “ice bucking”.

In the spring of 1902, the Edna Brydges was overhauled for her work between Rat Portage, the Black Eagle Mine (in Regina Bay) and Whitefish Bay. On May 7th she set off for the mine, bucking ice nearly all the way. When night fell, a fierce gale set upon her, trapping her in the middle of an ice pack. The captain cut the engines fearing that the propellor blades would be stripped and the Edna was left to drift. The greatest fear of the crew was that the floes would carry them onto a reef. Their dearest hope was that they would be carried into open water.

Fortunately when morning arrived the wind had shifted favourably, moving the ice away from the boat’s stern and allowing the Edna to head straight into the ice field with a clear propellor.

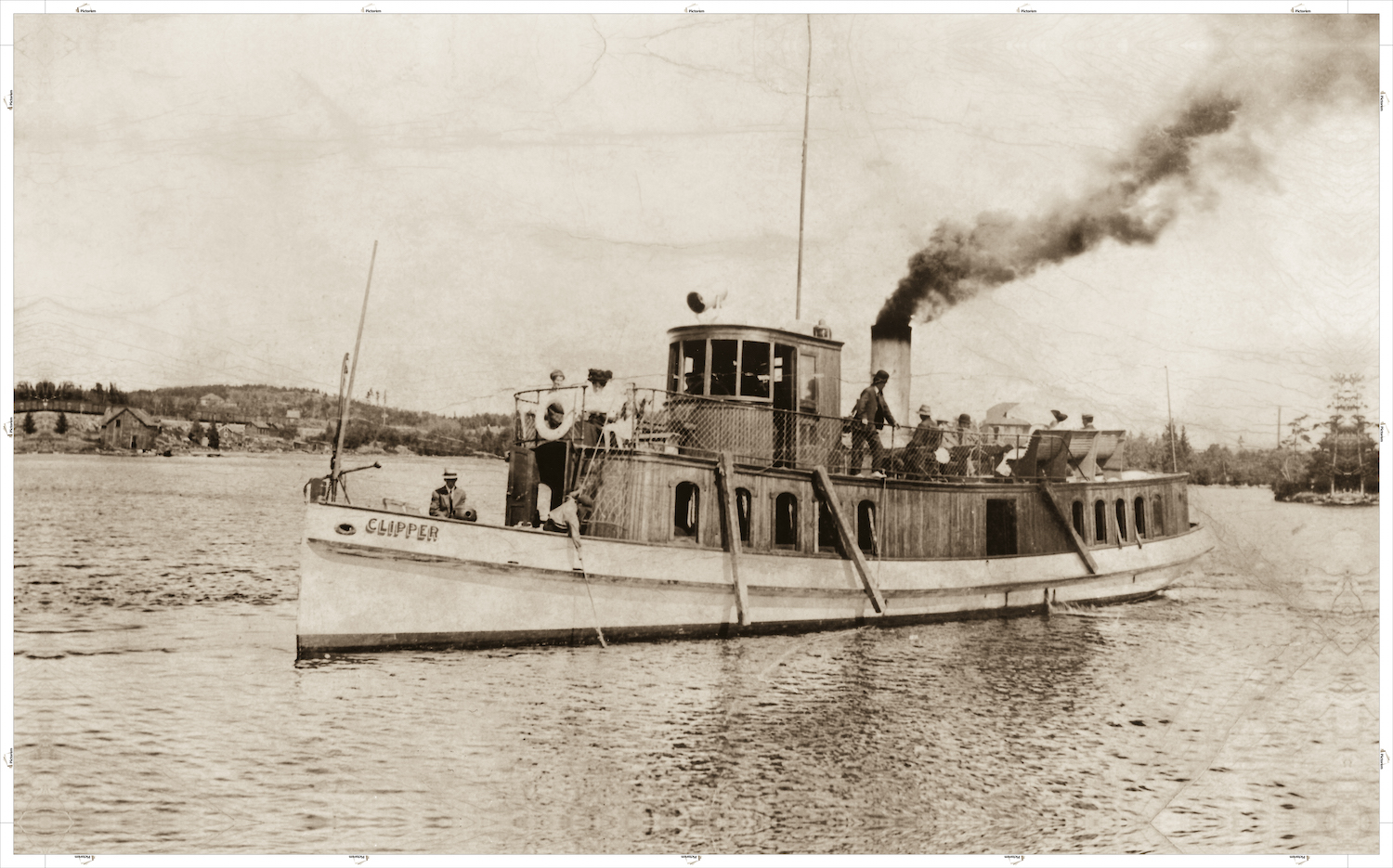

Meanwhile, back in Rat Portage, news of the Edna Brydges’ departure came to the captain and crew of the Clipper. They immediately boarded ship and headed for the Black Eagle Mine hoping to arrive there first. While the Edna struggled through the ice at about one knot per hour, the Clipper chugged along unhindered, thanks to the ice-breaking efforts of her rival. Eventually the Clipper overtook the Edna Brydges who was continuing her assault on the ice pack ahead of her. Captain Kendall of the Clipper chose a less toilsome route. He steered his vessel towards a small channel which just accommodated her narrow beam and shallow draft. In she slid, and when the crew of the Edna caught sight of her again she was several miles ahead and sailing for clear blue water.

The Clipper triumphantly arrived at the Black Eagle Mine well ahead of the Edna, much to the amusement of her captain and crew. She picked up a load of passengers and headed back to Rat Portage, arriving in the afternoon of the same day she had set out.

On May 28, 1907 the Daisy Moore, captained by Tom Robinson, was the first steamboat into Kenora from down the lake. While Robinson had encountered a considerable amount of ice on the way in, he claimed that it was quickly disappearing and estimated that in a few days almost any point on the lake could be reached.

For being the first that year to open navigation, Captain Robinson was presented with a fine Stetson hat by The Workingmen’s Clothing Store. He spent the rest of the day strutting down the street, wearing both the hat and a broad smile.

In 1904 a wager with local businessmen brought Captain Lewis of the Argyle, a new suit, hat and watch when he piloted the steamboat into its dock at the foot of First Street on April 29th, a day ahead of that estimated by the owners of MacKenzie & Co., Graham & Co. and G.M. Rioch Jewellers.

The Clipper cleans up.

And so the competition continued. On May 9, 1934, a front-page headline announced that the arrival at the town dock of two boats, Ventures and Rex, owned by George Folster from French Portage, marked the official opening of the lake.

Today we still look for the first dark stain of water seeping through the surface of ice and snow. It signals that the thaw has begun. And while there are no Stetson hats given to the first skipper on the lake, we still thrill at the sight of the first kayak or canoe that braves the chilly waters and know that soon the ice will be gone again.

Did you know?

The Lake of the Woods is a remnant of glacial Lake Agassiz and contains 14 542 islands. The underlying Precambrian bedrock is one of the oldest geological formations on earth.