Polio in Kenora

The Muse Newsletter

Vol. 31 No. 1 – Winter 2021

by Braden Murray

My grandmother used to warn me to stay away from stagnant water. No doubt there are some reading this who recognize that solemn warning from their own childhood. It was a warning that she delivered to me in the 1990s, and to my dad in the 1950s. But it wasn’t muddy knees and wet shoes she was worried about— no, she was worried about polio.

This is the story of the last major polio epidemic in Kenora — the summer of 1953. Though it is a tragic story, it is also one of hope. In the coming months seniors across the district will be vaccinated against COVID19. Many of those seniors are the very same people who as children received the emergency first use of Jonas Salk’s life saving polio vaccine in the spring of 1955.

As we spend another winter locked in desperate battle with an unseen viral enemy, it’s helpful and hopeful to reflect on another time in our history when we fought and we won. Poliomyletis, otherwise known simply as polio, is a viral disease that causes nerve damage, paralysis, and even death. The disease mostly affected children, and those under five were especially vulnerable. Polio was first identified in Canada in 1910 and by the 1930s it had reached Kenora. The disease was most active from July to the end of November.

The first big outbreak in Kenora was in 1937. Little was known about the disease at the time and many, including the local experts in Kenora, believed the disease travelled via summer dust storms. In hindsight we know that’s not the case, but as a parent in 1937 imagine trying to protect your child from dust.

Through the 1940s the disease was kept out of the headlines by the war, but every few years there was a small outbreak or isolated cases. The post-war baby boom provided a target-rich environment for the polio virus to thrive and cases steadily crept up through the late 40s and into the 50s. In March 1953 Dr. Jonas Salk announced that he had discovered a vaccine for polio, but the clinical trials were only just beginning. Together with partners like the Connaught Laboratory at the University of Toronto, Salk would trial his vaccine in 1953 through the end of 1954.

In a cruel twist of fate, Canada suffered its worst polio epidemic in the summer of 1953, just months after the announcement of the breakthrough. That summer all of Canada was affected, but Kenora’s infectious rate, along with Winnipeg, was among the highest. The under-standing of the virus was a little better by 1953— no one was worried about dust storms anymore— but there was still a question of how you avoided getting sick. This is where my grandmother’s advice comes from. People knew polio was a virus and there was a rudimentary understanding of how it travelled. The idea that it came from stagnant water became popular around this time. And there was some scientific backing behind it. We know now that many polio infections came from accidentally ingesting infected fecal matter. Eating with dirty hands was one of the main routes of infection.

By the end of August 1953 there had been 47 recorded cases of polio in Kenora with two deaths. The neighbourhood of Lakeside was hit particularly hard. The epidemic was so serious that the start of the new school year was delayed for two weeks. In a front page column of the Miner and News that

August, local Medical Officer of Health Dr. L.M. Stewart explained that:

“there are many more cases [of polio] not reported. The virus of polio may be carried by individuals who show no signs or symptoms. Others may only have a slight illness and do not consult their doctors. At this time of year, especially when there is polio about, any case of “summer flu” should be treated with grave suspicion as the early symptoms of polio and influenza are almost identical.”

During the 1953 epidemic the third floor of the Kenora General Hospital was used as a polio isolation ward for acute cases, and St Joseph’s was used for less severe convalescent cases. The wards were staffed with nurses who volunteered to assist, and led by Jacqueline Mason. Jacqueline Mason had grown up in Kenora, and left to become a physio-therapist at the Red Cross Hospital in Calgary. She’d been home on holiday that summer when the epidemic broke out, and with the blessing of the Red Cross, she volunteered to stay and lead the local response. Physiotherapy was a fairly new field at the time and her unique skills were crucial in helping to get the children who were afflicted literally back on their feet.

In total there were 64 diagnosed cases of polio in the Kenora area during the 1953 epidemic. Of those 64 cases, seven had to be sent for special care in Winnipeg and four were sent for special care in Sault St. Marie. Sadly, two of the polio patients, both children, passed away.

Things did calm down through the winter of 1953 and into 1954. The aforementioned Salk vaccine breakthrough had been announced in March 1953, but it was taking a considerable amount of time for it to be produced at a large and safe scale. Still there was hope— in early reports from the clinical trials the vaccine seemed to be working.

As you might expect, going into the summer of 1954 local parents were quite concerned that there would be a repeat of the previous summer’s epidemic. At a meeting of the King George Home and School group in May 1954, the supervisor of nurses at the Kenora Health Unit, Hazel Wilson, addressed concerned parents. She explained the history of the virus, how it spreads, and how infectious it is. Additionally, she warned that the summer of 1954 had the potential to be even worse than 1953. Finally she mentioned how critical it was that the fear the parents were feeling not be transmitted to children since it might harm them psychologically in the long run— a savvy and appropriate message in childhood development that’s applicable even today.

Luckily the summer of 1954 saw only a handful of polio cases, not just in Kenora but across Canada. There were only two confirmed cases across the district— one in Redditt and one in Kenora. Considerably more people were killed and injured in motor vehicle accidents that summer— shockingly 20 people were killed and many more were injured in July and August alone.

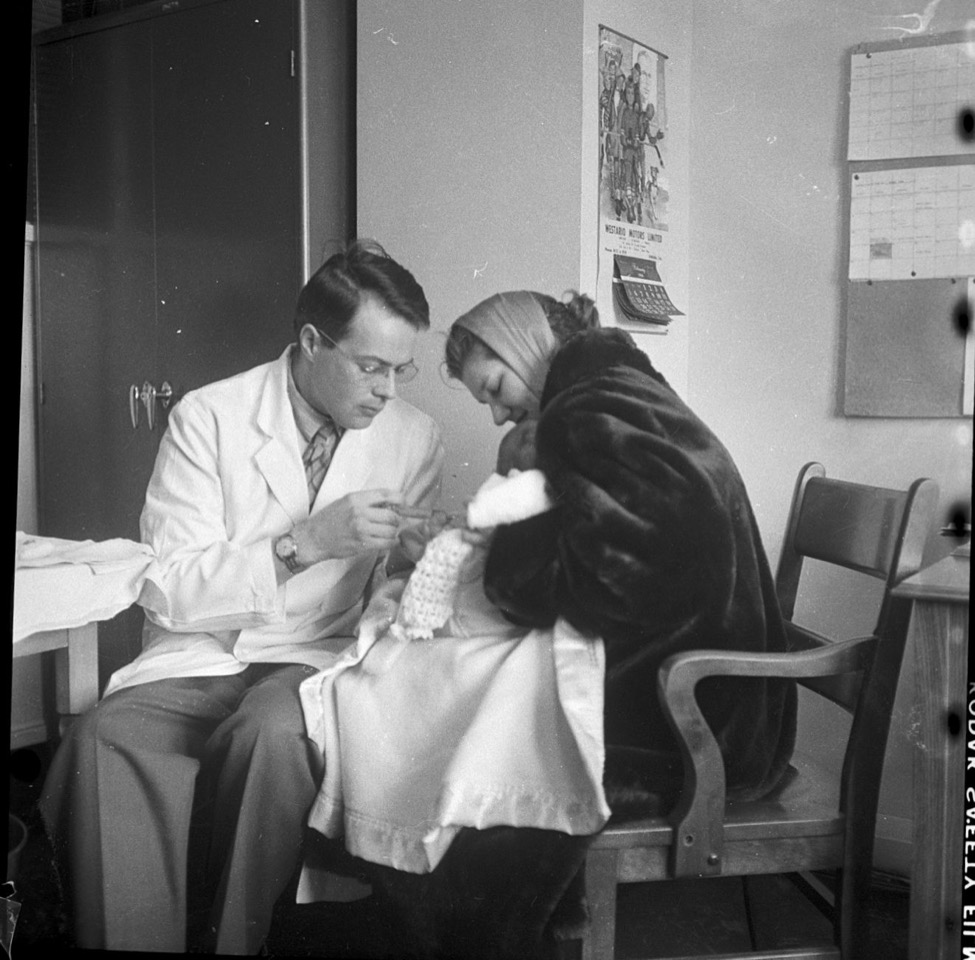

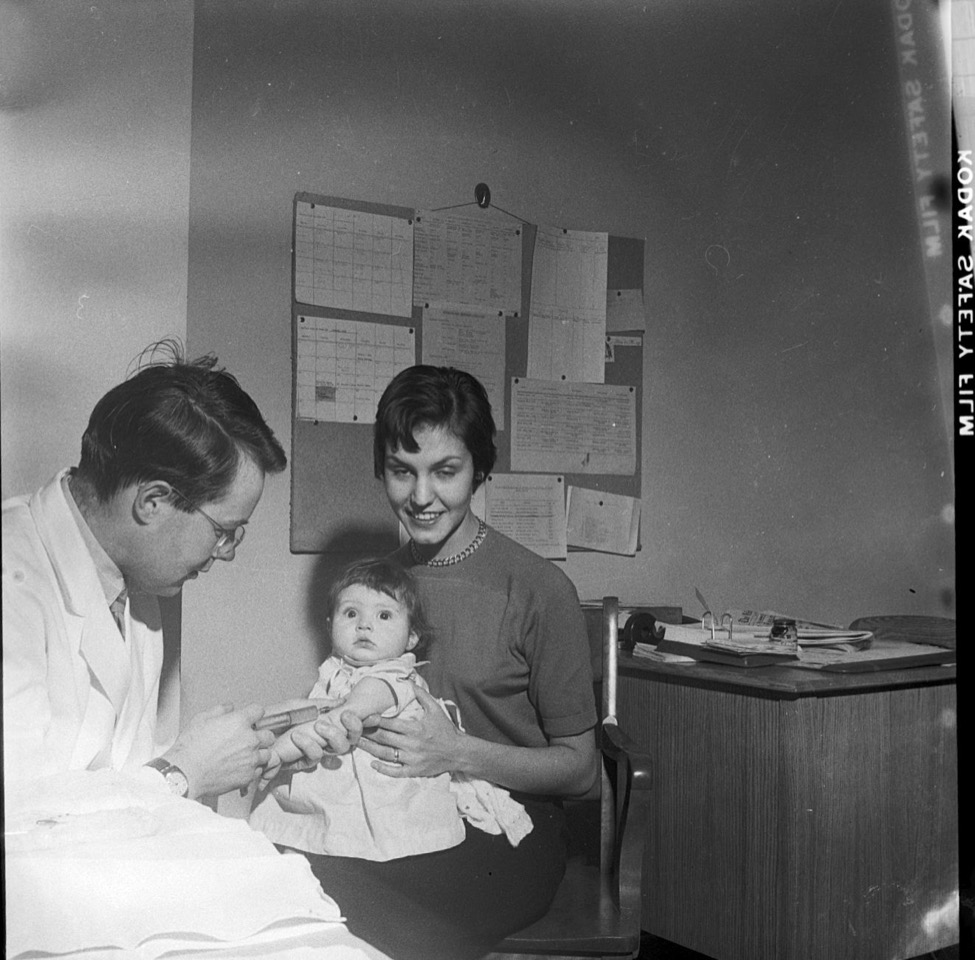

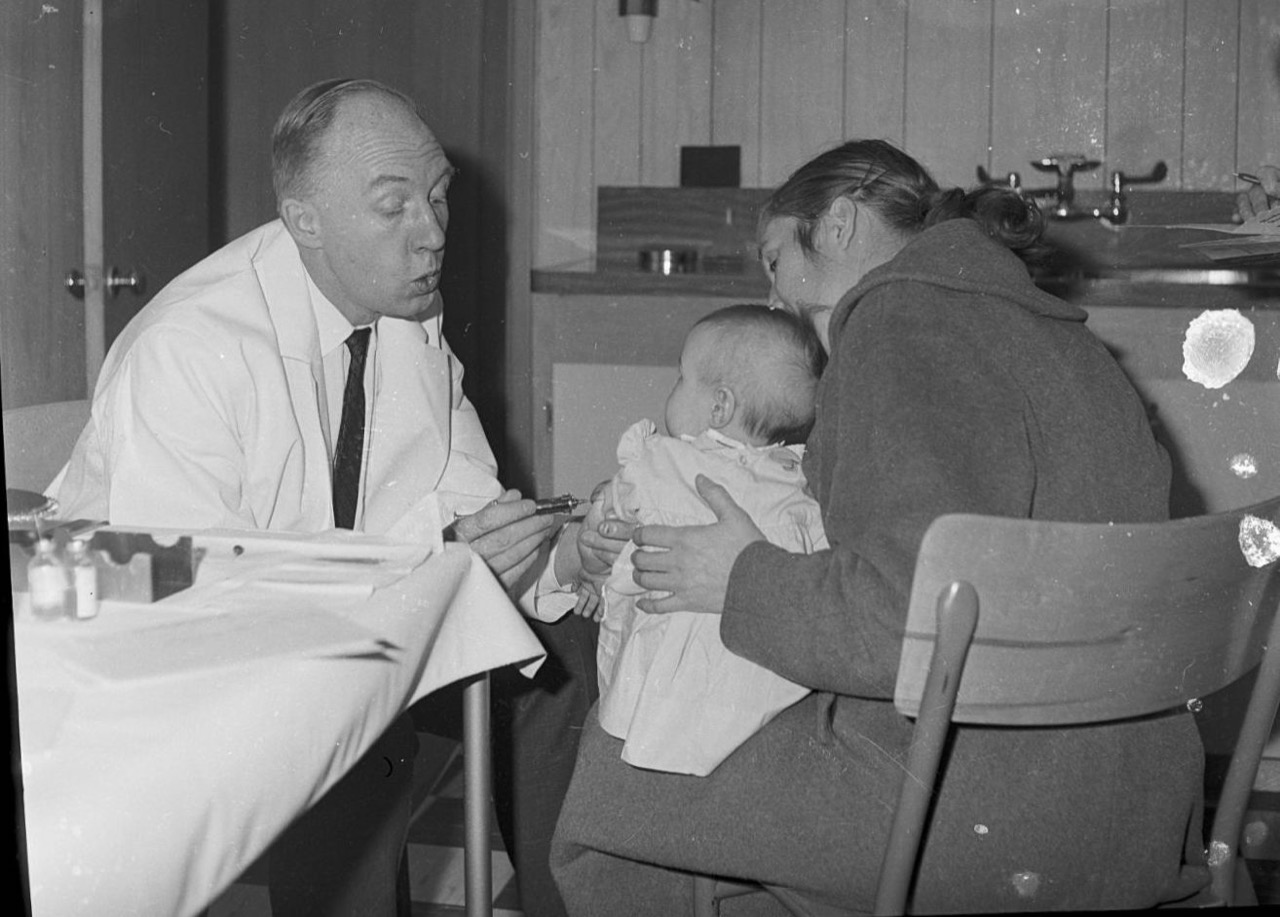

During the summer and fall of 1954 and into 1955 the Salk vaccine was undergoing successful trials. On April 12th, 1955 the Salk vaccine was certified as both safe and effective. That same day the Kenora Health Unit announced that all local grade 1 & 2 students would be vaccinated in cohorts at their schools in the coming weeks. When more vaccine was available all students in primary and secondary schools would be vaccinated. The vaccine program was completely free of charge through a federal-provincial partnership. Ontario Premier Leslie Frost said of the vaccination program, “This is the soundest investment we have ever made. We’re not going to fool around. We’re going to get this moving as fast as possible.”

The Salk vaccine required multiple doses, so the first local vaccinations were completed in mid June 1955. From there vaccinations were carried out every year. Eventually an oral vaccine was rolled out, and by the 1970s polio was uncommon in Canada. Helping this cause were organizations like the March of Dimes and Rotary International, including the Kenora Rotary Club. Together with partners they have raised millions of dollars to help eradicate polio worldwide, and those efforts continue to this day.

We are once again in the midst of a great public heath emergency, but just like in the 1950s, help is on the way. We’ll stay at home and wait patiently for vaccinations to arrive in the next few months, and who knows, maybe a few alumni of the original 1955 class of the Salk polio vaccine will once again lead the charge into the future.

Did you know?

Walter J. Phillips visited Lake of the Woods in the summers of the 1910s -1920s. This distinctive landscape would serve as inspiration until 1940.