McLeod Park

Lake of the Woods Museum Newsletter

Vol. 13 No. 3 – Fall 2003

by Lori Nelson

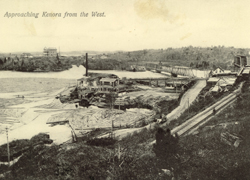

There’s a small parcel of land situated between downtown Kenora and Tunnel Island that, in its history, mirrors a substantial part of the development of the entire area.

McLeod Park wasn’t always the gem of a park that it is today. Its serenity once shuddered with the pound of stamps pulverizing ore. Its ornamental grounds were covered with a forest’s worth of wood chips and piled lumber, and were criss-crossed by roads and overland tramways rather than brick footpaths. It has fallen victim to fire twice, been expropriated, and has finally become a summer showpiece and tourist attraction. Gold mining, lumbering, the railway, the highway, and finally tourism have all left their mark on this small bit of land.

When gold was discovered on Lake of the Woods in the 1880s, prospectors, miners, surveyors, and investors flooded into the area referred to by one expert as the most promising gold region in America. Everyone wanted a part of the action and companies were being established with that in mind.

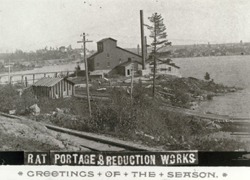

In December of 1889, the Canadian Milling and Reduction Company was organized in Chicago under the laws of the State of Illinois. The following month, they began construction of a reduction works on that small parcel of land east of what is now the Hospital Bridge. Later that year, the company was reorganized under an Ontario charter as the Lake of the Woods Gold and Silver Reduction Company. Their intent was to treat 30 tonnes of ore a day from the mines on the lake and with that assurance, the town promised them an incentive bonus of $10,000 upon completion of the mill.

The reduction works consisted of a 20-stamp mill, chlorination plant, stables, docks, tramways to the Canadian Pacific Railway, and a complete system for reducing ore to bullion.

When the mill was completed in the fall of 1891, it was reportedly capable of handling 191.5 tonnes of ore per day. In fact, during its one year of operation, the mill processed only 75 tonnes of ore from Sultana Mine and another 5 tonnes from the Pine Portage Mine, according to a Bureau of Mines Report published in 1894. Mismanagement, careless handling of the ore, and internal strife between the president of the company and the mill manager were cited as reasons for the short life of the mill, which closed in August of 1892.

The property sat idle for several years and went through several hands, including a mining company and the Dominion Gold Mining and Reduction Company. In 1899, there was talk that Robert Ahn, a local mining broker, and several of his associates were contemplating purchasing the plot of land and constructing a first-class hotel there. The site was considered ideal, particularly since it was to be on the line of the proposed electric street railway that was to run between Rat Portage, Norman, and Keewatin. The plan for the hotel fell through, as did the plan for the street railway.

The derelict mill continued to occupy the site until April 26, 1906. The following day, the local newspaper had this to report:

Twenty twisted steel stamps sticking up from amongst the pile of bent metal, fallen brick and burnt woodwork, is about all that is left of the fine reduction works that stood just above the town’s power house on the Winnipeg River yesterday morning.

The mill, stable, offices, tramways, and some of the docks were all destroyed in the scorcher. The alarm was rung mid-afternoon when thick smoke billowing westward from under the tramway was noticed. The flames spread quickly and it was only through the efforts of the fire fighters and a bucket brigade that the two residences on either side were saved.

The value of the property destroyed was estimated at $50,000 with neither the buildings nor the contents being covered by insurance.

Entering the picture was lumberman John W. Short, who purchased the land that year and in the fall, started up his tie mill operation. The fire site had been cleared and a building constructed and machinery installed. The site couldn’t have been better for such a venture. Logs were boomed in from the lumber camps down the lake. They were then run up from the boom on a jock-ladder to the site, where they were sawed to regulation tie length. From there, they were conveyed to a large saw, which trimmed two sides flat and then were placed on a large conveyor that took them to the CPR siding just up the hill. The conveyances meant that there was next to no handling of the logs from the time they left the water until they were in place for loading on rail cars. The ties supplied by the mill were used in the double tracking of the railway.

But fire once again intervened. The mill burned to the ground in 1914. Short sold the property to the Keewatin Lumber Company in 1921, who transferred it to the Backus-Brooks Pulp and Paper Mill in 1925.

Development of the site as parkland came in the years following. Sod was laid, trees and gardens were planted, benches were placed. It was named in honour of Dan McLeod, one-time owner of the Rat Portage Lumber Company and later, general manager of the paper mill.

Originally, the roadway running from Kenora west towards Norman ran along the south part of the railbed, but in 1958-1959, the new hospital bridge was constructed south of the original one, and the road was reconfigured to suit this adjustment. In order to do this, some of the parkland on the east side of the bridge was expropriated by the Department of Highways, greatly reducing the size of McLeod Park.

In 1967, the Chamber of Commerce commissioned the building of a 40-foot replica of one of the largest fish found in Lake of the Woods. Jules Horvath was responsible for the design and construction of the town’s symbol, Husky the Muskie, which became the focal point of the park. But Husky is no longer the only feature attraction of the park. The tugboat James McMillan now sits in drydock, testament to the site’s early history in the lumbering history of the area.

Today, the park is a draw for tourists, whether it’s to stroll through the park, to catch the big fish for holiday photo albums, enjoy the beautiful gardens, or relish a picnic lunch in the shade.

They’re perhaps not aware that where they stand represents a microcosm of the area’s development that the rocks sparkling along the shoreline may have a hint of gold; that the CPR railway across the Trans Canada Highway transported the ties sawed on site; and that fish, maybe not quite as large as Husky, are one of the key draws for visitors to the area, as is the lake on which the little park sits.

McLeod Park has much to say, in its own understated way, about our history.

Did you know?

Both the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company operated on the Lake of the Woods, and would often sabotage each others equipment at portage sites.