Blood on the Snow in Rat Portage

The Muse Newsletter

Vol. 30 No. 1 – Winter 2020

by Braden Murray

This is a true story of life and death in Rat Portage taken from contemporary accounts.

Thomas Drewes was a simple man. At 37 years old he spent most of his life in Europe before immigrating to Canada some time in the 1870s. He was a burly man of Prussian stock, over six feet tall with a flaming red beard and soft grey eyes. He spoke broken English that was often difficult to understand. Though a quiet man, he was known to have a violent temper.

Drewes moved to Rat Portage in the fall of 1882 and found work as the chore man of the McKeown boarding house. Described at the time as the “hardest den in the northwest,” the McKeown boarding house was operated by the widow Mrs. Elizabeth McKeown. She and her husband, who had drunk himself to death the previous September, were both well known to police. Rumour had it that whiskey flowed freely in the house, and several women worked for Mrs. McKeown as prostitutes. The McKeown boarding house was one of several in Rat Portage that lined Matheson Street and Hennepin Lane that catered to the young, single men who worked on the railway. One such boarding house, the Albion House, can still be seen as part of the south end of the Lake of the Woods Hotel building.

One of the residents of the McKeown boarding house in late 1882 was a young Irishman named Patrick Maloney. Having come to Rat Portage from the Ottawa area, he worked as a railway hand on the construction of the CPR. At only 22, Maloney already had a reputation of being “boisterous when under the influence, and by no means gentle when sober.” Thomas Drewes’ thick accent and quick temper made him a favourite target for Maloney’s bullying.

Patrick Maloney spent January 1st, 1883 celebrating the new year at a local saloon and came home to the McKeown House that evening in a “beastly state of intoxication”. At about 11 p.m. he went into the kitchen looking for a glass of water. Thomas Drewes was in the kitchen and told Maloney that there wasn’t any water in the house. This was before indoor plumbing and water had to be fetched from outside or bought by the barrel. Despite this, Maloney wouldn’t take no for an answer, and called Drewes a rude name while demanding a drink. Drewes responded, “G__D___ you, I will give you something to drink!” while swinging a piece of firewood at the young Irishman. Pat Maloney was able to dodge the blow and told Drewes that he was “too drunk to fight now, but if he would wait until the next morning then [they] could have it out.”

The next morning Thomas Drewes woke up early to cut wood, fetch water, and do his morning chores. Maloney asked Drewes if he was “as good a man as he was last evening.” Drewes said he was and went out the back door of the kitchen. As he left, Drewes armed himself with the lid lifter from the wood stove which he later exchanged for an axe. Maloney wasn’t aware that Drewes had armed himself because he was taking off his waistcoat in the sitting room— blood does stain, after all.

There are conflicting accounts of exactly what happened next, but the witnesses all agree on a few details — Patrick Maloney left the house by the front door. He walked through the alley between the houses to the back of the building. As he rounded the back corner of the house, Thomas Drewes swung the axe striking Maloney in the head. Mrs. McKeown’s son, James, watched the fracas and yelled, “Oh Tom. You’ve killed him!” But Maloney wasn’t dead, at least not yet.

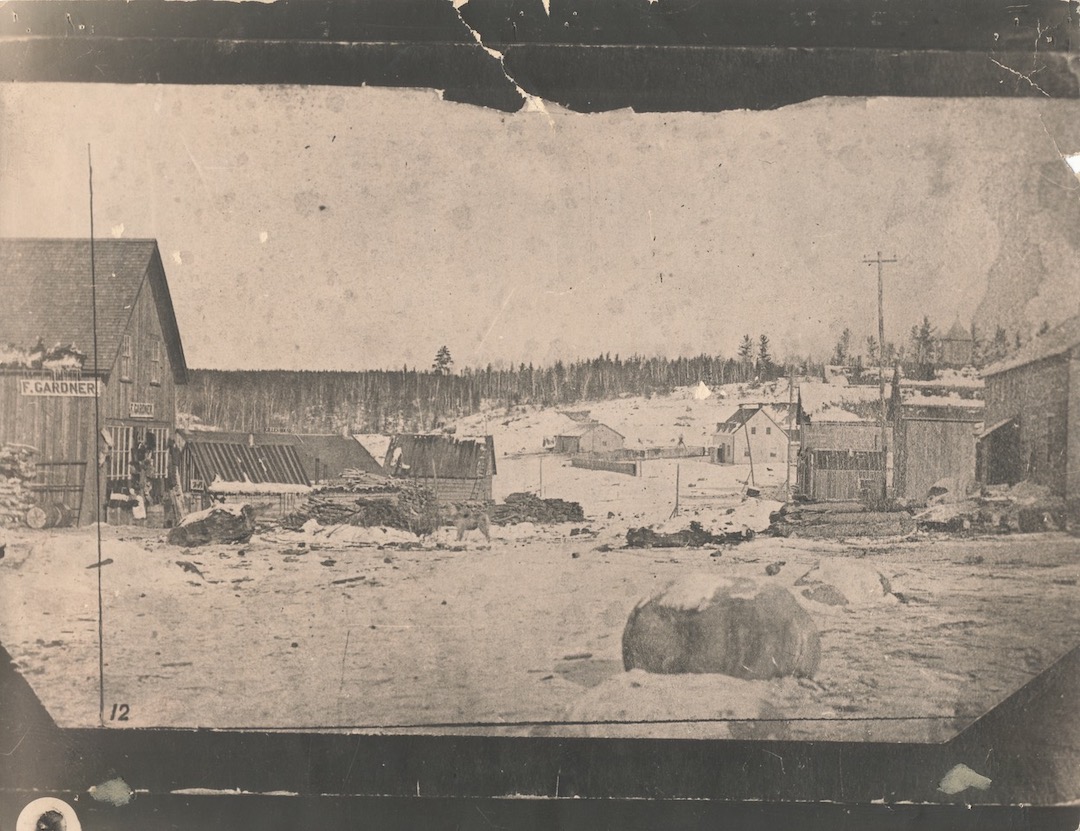

Main Street, facing North.

At 7:00 a.m. on January 2nd, 1883, Police Constable Rupert Donkin was awoken by a knock at the door. Standing in the doorway was Thomas Drewes. After wishing the constable good day, Drewes said, “Mr. Donkin, I have come to give him up.”

“Give who up?” replied Donkin.

“I struck him with an axe.”

Well that got Constable Donkin’s attention. He got dressed, and hurried out the door. At some point Drewes mentioned the McKeown house. Donkin knew it well. On arriving at the house, Donkin found a crowd of people, including Dr. Thomas Hanson, surrounding a man with a severe head wound. The man was conscious and in fairly good spirits, all things considered.

The wounded Maloney, Dr Hanson, and Constable Donkin went back to the kitchen and found Drewes watching the scene unfold from behind a cracked door. It was clear that Drewes had come to turn himself in that morning. “Thomas,” said Constable Donkin, “if you come with me I will take care of you.” With that Drewes joined Constable Donkin and they walked to the jail at Main Street and Third Street South.

Despite being alive at the moment, it was clear that Maloney’s wounds would be fatal. Soon a crowd was assembling outside the McKeown house. Cries of “Lynch the murderer!” and “Shoot the assassin!” were heard as the mob marched toward the jail.

From his modest chapel just north of the railway tracks, Father Jean Baptiste Baudin, the parish priest of Notre Dame du Portage Catholic Church, could likely have seen the crowd. He ran down Matheson Street to meet them at the jail. After a few tense minutes, Father Baudin convinced the crowd to disperse.

Later that week Thomas Drewes was transported to Winnipeg. On route it was discovered that inflammation had set in on Patrick Maloney’s wound. He died on January 11th, 1883.

Drewes, adamant that he was afraid and had acted in self defence, was, nevertheless, now facing a charge of murder. If found guilty, he would be hanged. At trial, Drewes was defended by former Attorney General of Manitoba Henry Joseph Clark, a Winnipeg lawyer that was well known to take difficult cases (he would later defend 25 members of the 1885 Riel Rebellion).

There is another layer to this sad story that is something that the modern eye could easily overlook. In several of the pieces that describe Thomas Drewes, it is mentioned he is a “simple man”. In the context of a court case in 1883, being called a “simple man” likely meant that Thomas Drewes suffered from some form of intellectual disability. His fiery temper and history of violence, (Maloney was not the first to be attacked), combined with Drewes’ misunderstanding of social norms and customs paint a picture of man who was suffering and excluded by a society that didn’t understand his special needs.

When the case went to trial in March of 1883, there was no doubt that Drewes had committed the crime. At issue, however, was whether there was malice in his actions – in other words, would the sentence be for murder or manslaughter. There were several eye witnesses who testified, and all described a scene of desperation, anger, and confusion. The verdict was returned only a day later on March 14, 1883 – Thomas Drewes, guilty of the crime of manslaughter.

In explaining his decision, Justice Wallbridge made clear that Drewes was clearly feeling threatened the morning of the attack. A witness had come forward who was a friend of Patrick Maloney, and it appeared to the judge that Drewes felt like he had been “surrounded by foes on every side.” Finally, Justice Wallbridge said it was clear that “the prisoner is alone in the world, and [does] not understand the English language.” In closing the Justice expressed his profound sympathy for Thomas Drewes and his situation, and because of that sympathy he gave the smallest term the law allowed – seven years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary.

The epilogue of this grim chapter of Kenora’s history fits the same unfortunate theme of the rest. Thomas Drewes was a well-behaved prisoner at Stony Mountain, and much like at the McKeown house, was employed by the guards as a chore man. He was a model prisoner, but was susceptible to fits of melancholy and always maintained that he had only acted in self defence. On December 17th, 1883, eight months into his sentence, Drewes finished his chores, and returned to his cell around 6:00 p.m. When the guard left to fetch the prisoners’ supper, Thomas removed his suspenders, tied them to a bar at the top of his cell, fashioned the other end into a slip knot and hanged himself. When he died Thomas Drewes was about 38 years old.

Did you know?

The Lake of the Woods is a remnant of glacial Lake Agassiz and contains 14 542 islands. The underlying Precambrian bedrock is one of the oldest geological formations on earth.